A Brief Explanation of a Pause:

There are times when artists create and times when artists are limited to experience. Creativity ebbs and flows, time is stolen away by intruding opportunities and the influence of others. We must work; we must wander. We walk with hearts open. At times when we are free, we give and give. At other times we must close off and retreat, pulling deeply into ourselves to find the parameters of what it is that must be created. We seek, we become. We are only what we have always been. It is in this that we offer the pieces of ourselves to each other, gathering and increasing in the fury of life and the continuance of existence.

It’s been a few months since this blogger has written anything, and in apology she is offering this anecdote: Upon reaching the green shores of the Kingdom of Éire, a writer met a musician who asked her to sing. She was supposed to visit Ireland for a week. She stayed for a song. She sang for another. She sewed together the pieces of her heart and struck her finger on the stitching. She thumped a beat and he strummed a tune. They sang together and people listened. She was moved. Paths were abandoned and new passages formed. Time increased its rapidity, rather than slowed, communication and habits of old abandoned in new pursuits. Such is the way in a life lived wide open.

Committed to family and friends in her homeland, she returned home for weddings and holidays. He followed for a breath. They sang with her sister, who joined in with her oboe. They were rewarded with opportunity and met it well. Time paraded on and the end of a chapter was met; the beginning of another faced.

Though the current focus has shifted to music, the enduring passage remains in writing. Remember, then, that everything is temporary. We are here, here are we. We depart and we return. The writer pauses for a breath and waits for the moment the writing is to be continued. The song carries us through our breath and gives us hope, and joy.

Musicians, Artists and Rebels, the lot of ’em: the Kingdom of Éire

Ireland: the land of music and laughter. Unlike many of my American friends and acquaintances, I don’t have Irish roots. I never truly felt the magic of St. Patrick’s Day, my family has been Lutheran for as long as time, my skin turns a lovely shade of brown in the sun, and my only association with red hair is an enduring adoration for the classy sass it portrays when paired with lipstick and freckles. However, as luck comes to luck, I was plopped onto a ferry at Holyhead, headed for Dublin, with no plans, no lifetime ambition for coming to Ireland, no idea what I might want to do or see.

And here I am, two weeks later, gradually getting my socks charmed off by the hospitable and humorous Irish. Galway, with the sunny cobblestoned streets full of gorgeous young musicians: a beaming tap dancer, a duo paired on harp and Irish accordion, a street performer with genuinely hilarious jokes, four boys in green traditional vests with smiles as big as the sun. A little old lady stopped by me as the crowd gathered on the street to watch the band, the cello player dancing as he played, all four whooping together with giant, contagious grins: “Aren’t they lovely, then?” she smiled at me, “Even me, I’m old and oh, aren’t they just lovely? God bless them.”

After a quiet celebration of the fourth of July–American flags dancing in the streets outside the pubs, possibly united by the common joy of escaping British rule–we moved on to the Aran Islands, to Inis Meáin: desolate, totally unique, known for its truly preserved use of Gaelic, unlike anything I have seen in the world. “God’s country, that is,” an Irish woman told me in the market after starting conversation with me when she saw me looking at wines. “It’s incredible, I haven’t been in years, but my memories of it… I first went when I was 18, and then again when I was 28… I’m always waiting to go back.”

“The end of the world, it is,” another woman said. “Just drops off there, you know. That’s the edge of it.” And the island is silent, not polluted by traffic sounds, only the quiet buzz of the few electric poles that run alongside the two perpendicular roads, very few bird calls, the occasional echoing moo of a cow a mile away. The island is covered by walls: rock walls four to five foot high, dividing the small rocky isle into hundred upon thousands of miniature square plots.

“Well, some of the walls are for property division, of course,” the man at the B&B informed us. “But I do believe some of it is for surface clearance,” which really got us cracking up, despite the truth of it. The island is basically a mass of rock, which over the last hundreds of thousands of years people have been breaking up into smaller chunks of rock, which are piled into walls, thus clearing the surface for plants or livestock: two cows here, a couple of mules across the way, the occasional bleating sheep. One day we left with the intention of walking completely around the island, which led us through a seemingly abandoned countryside of walls. We crossed an ancient fort (of piled rocks), along the coastline (where we stopped to eat in a sheltered cove of piled rocks), to the entirely desolate opposite side of the island, where we stumbled across the most incredible, staggering display of seaside cliffs.

Cormorants washed and played in the waterfalls as they splashed down alongside the cliffs, seagulls effortlessly gliding above the view, curiously cocking their heads to look at me as they passed. A fresh spray of salty mist splashed againt my face as I crawled close to the edge. Not a soul in sight, and possibly the most breathtaking landscape I’ve seen in my life. We walked along the coast for at least an hour, drinking it in, not seeing a single other person in the whole time we were there. After some time, the coast flattened down back to sea level and we attempted to cut inland through the labyrinth to make it back to the one road on the island: after 20 minutes of walking, we were clearly trapped and had to retrace our steps back to the coastline. So many walls. Could drive one to insanity.

Dublin has become an international city, like so many other European capital cities: flush with diversity, innumerable languages on the street, vibrant with city life, totally illogical traffic signaling that often leaves pedestrians stranded on concrete islands in the middle of opposing lanes of rushing traffic. Everything ‘Irish’ is bartered at a price: culture and history branded for money, authenticity replaced by flashing tourist traps at exorbitant prices, everyone is a tourist and everyone is drinking Guinness. I met only the occasional Irish lad working in the pub that was able to lighten up the scene by cracking jokes.

So I escaped south to Wexford, in a quiet town tucked just off the beach*, right on the coast of the Irish Sea. I spent my birthday laying on the beach and swimming in the salty sea, floating effortlessly at the surface of the water. In the pubs here everyone drinks Heineken or Carlsberg, possibly capping off the night with a Guinness. The pubs are full of laughter and music: it seems to be a requirement that the music be played live, cover songs and requests, the occasional jaunt into rebel songs and traditional folk songs a must. Jokes are played at the offense of friends or neighbors, the beer flows strong and everyone has a laugh waiting to surface: “Bloody hell, man, whaddya’ doing wearing my shorts?” yelled one very tall man to a much shorter man in high-waters, causing the two tables to roar. “Make sure you put ’em back just where you found ’em!” In another pub, a friend of a friend is a musician, his voice for singing, curly red hair cropped close to his head, reddish-blonde stubble on his face, eyes glowing with mischief and humor, a sort of restlessness in his motions: he told stories like a god, perfectly painting the scene and inviting the listeners in, humor evident throughout. I hung on his words, “Tell another story, please, would you?” and we delved into conversation about stardust and the luck of the universe. His friend was a realist painter, trained from a young age: “What was his name, again?” I asked, met only with, “Ah, I donno man.” Which I confusedly but solidly believed.

Trailing from gig to gig, we ended up overlooking the coastline as the sun began to set. There were about six of us, all ages, sitting on the picnic benches with a pint: conversation flowed into songs which flowed back into conversation. Effortlessly, one person would start to sing and suddenly we’d all join in, clapping and snapping along. The light was sucked slowly out of the sky and absorbed into the water, transforming from deep steely blue to a pink-tinged silver. Someone grabbed a guitar, and then another person went to his car for a banjo, and we were joined by some men from a nearby pub, who sang and clapped and threw out compliments: “I loved your voice there, the way it blends with the guitar. It’s really lovely, that is.” And as we retired at the end of the night, everyone was appreciative and kind, inviting the musicians to come back, wishing everyone well as we floated off to our respective places.

Musicians and artists and rebels, the lot of ’em. It’s the people that make Ireland, just as I’ve always been told. A hidden charm, buried in kindness and humor. Give it time, let Ireland soak you up. And the longer I stay, the move evident it becomes that there is something undeniably unique about this Kingdom of Éire, land of musicians and poets and artists, this misty green, gorgeous island settled in the ocean at the edge of the world.

Another week or two of vacation in Ireland for me and then it’s back to chasing trains in Scotland. Cheers, to your good health! Moving on today to the south of Ireland! Sláinte!

*Apologies from the writer. A misstatement regarding the town of Riverchapel was written based on rumor and not fact. I had a relaxing stay in the Beaches Youth Hostel (more like an apartment share than a hostel) and would highly recommend a stay to anyone looking for a peaceful day or two tucked away from the city and near the beach.

Trainspotting the Scottish Highlands

We leave at 5.30 in the morning from North Queensferry. I sleep in the front seat until we begin winding through the start of the highlands, the hills are dramatic as they rise and fall as far as the eye can see. Our arrival at Fort William is simply to scope out the engine, shunting on the tracks: Black 5 no. 45407, the Jacobite, built in 1936-7 for LMS (London-Midlands-Scotland) in Crewe, privately owned and contracted to West Coast Railways for the six-month tourist season to run from Fort William to Mallaig. It’s a gorgeous engine, shining black steel, massive cast iron wheels connected by forged steel simple-linkage rods, healthy exhaust as the train primes.

We set off to Corpach Basin, to have a brisk walk along the lower loch and watch the departure of the train from across the lake. It’s off in perfect time, 10.20 on the dot, steam blowing, a line of exhaust tracing across the cluster of white, fort-like buildings arranged on the hillside that composes Fort William. We reverse direction, pick up the pace and return to the Basin, past the ducks quacking as they skim across the lake and the boats bobbing between the bridges in the canal space of the seventeen lochs, waiting for their chance to rest in the lower loch.

A crowd is gathered in the parking lot, cameras at the ready: the engine sails through, giving a whistle of greeting, exhaust beautifully stretched out behind. The windows are full of smiling faces, everyone waving, six red carriages and then it is gone, racing along the lake and out of view. We jump into the car and we’re off in hot pursuit–leaving Coprach and racing through villages, overtaking cars and lauries on the motorway and before long we are next to the train, racing beside it as it flashes though the trees, slowly overtaking the carriages and the engine is barely visible, the powerful barking sound resonating through the air, chugga-chugga-chugga, the exhaust billowing and the red bodies of the carriages flashing, windows perfectly placed inside them, faces seemingly frozen beside us as our speed matches and the route changes, the train disappears behind the hill and we are alone, racing on the road, buried in the trees.

We race on. “A turn on the right, and the lay-by just after it,” John repeats to himself, a road flashes by on the right and he slams on the brakes: “Seatbelt off, dearie, saves a few milliseconds,” and we pull off the road at Fassfarn, jump out of the car and John grabs his camera, we jump over the fence, race across the track, clamber over the second fence and we are in a field, sheep grazing to the right and Loch Eil stretches up to the base of the railway on the right. “We’ve got a few seconds here,” John tells me, and, “Oh, look at that spot of sun!” and he is visibly excited, walking in his rushed, bouncing gait to stand beneath a tree and situate himself with his camera.

The sound reaches us first, a-chugga-chugga-chugga, the engine is working and for nearly a minute we are bouncing with excitement and anticipation: a glimpse of exhaust in the trees in the distance and, “Wah-hoo! There it is!” and the engine races beautifully out of the woods towards us, the sounds and the sight and the sun peeks out and it races past, faces waving in the windows and we are buried in the field, laughing and waving as it races by.

“Very good, carry on,” says John and we race back over the fences, across the tracks and back to the road where we rush on, eating wine-gums and hooting and hollering and laughing, racing down the sprawling roads and John starts chatting and drives slightly slower and we miss it at Craigag bridge, getting just a glimpse of the tail end as it races along the hillside and into the trees out of sight and we speed along. “We’ll catch it tomorrow!” I exclaim with a whoop.

We race on to Glenfinnan, where all the tourists are clustered at the base of the hill: John drops me off at the edge of the parking lot and I sprint out of the car, laughing and running in sheer exhilaration, and just as the train reaches the start of the viaduct in the distance it slows down, lets out a stream of exhaust and whistles for the crowd, everyone cheers and as it disappears on the other side of the epic valley I race back to John, jump in the car, and we’re off again.

And so it goes, for three days, chasing the trains from Fort William to Mallaig and back again, climbing through the wild, rugged highlands, making our way through ferns and boggy mosses, over the cliffs to see hidden parts of the railway, pruning back the trees that distract the view of the train: being eaten by midges, searching for ticks, no time for food in the day as we race after the morning train and afternoon train and in the evening we enjoy meals of fresh seafood or fish and chips before I go to rest in the Bed & Breakfast and John drives off to sleep in the car and bathe in the river, he enjoying his ‘wild living’ as I bask in the glorious luxury of a hot shower, a brief time of quiet and rest before a proper breakfast early in the morning and the call of the whistle to roil our blood and entice us to follow.

“It’s super! It’s wonderful! It’s excellent!” John yells in his excited English accent, pumping his fist in the air, reaching and exceeding the speed limit for the first time since I’ve met him. “It’s all in the chase! Who-hoo! Just knowing it’s coming! Who-hoo! Oh, wonderful, dear. Just wonderful. Fantastic! Ho-ho! Who-hoo!”

And I giggle and whoop and holler along with him, and roll down the window for the refreshing flood of energy that accompanies the pursuit of the barking and whistling steam engine.

Trains: Racing Through the Craiggs

Useful Things.

A handful of useful sites and resources that I take for granted being familiar with, now gathered up to present to you: keep in mind that this is primarily Europe-based travel advice, as I am at this time primarily traveling through Western Europe and the UK.

I travel cheap. Dirt cheap. Sometimes all I eat is bread, for weeks, until I can’t stand the thought of cutting up another piece of cheese and ripping off another piece of bread and putting it in my mouth to thoroughly masticate before the sodden lump retreats down my throat to my grumbling, endlessly crying stomach. Brief relief: apples. Cream cheese and tomatoes. Different types of cheese and bread as per the country. Always buy enough for the day, and buy it fresh again in the morning. Local bakeries are best. Splurge and buy good jam. Carrots. Make pasta occasionally. Splurge and buy ingredients necessary to make a great dinner. Avocados can be a great relief. Canned artichoke hearts are a cheap and tasty snack. Take your own loose leaf tea and make it as you go: hot water is always free.

Lodging: if you have time and not money, look into WOOFing to do some local organic farm-stays or find a job through sites like WorkAway. Otherwise, stay with friends you meet along the way. Always take the contacts of people from interesting countries, especially those you like. Travel-minded people love to host and travel to meet other travel-minded people. Couchsurfing is a great site, which some people avidly swear by. You can get the occasional loose screw, but be smart about how you travel, always have an escape plan in the back of your mind, and be critical and selective when choosing who to stay with. Hostelworld is the next step up, which is pretty much the only site I use when searching for hostels. Search by price, read the reviews (I hate mildew and generally do my best to avoid mildew-ridden-comment places) and book from there. Generally the cheaper prices you get online are not available if you just impromptu arrive at the hostel desk: and as you pay a booking fee through the site, it is best to book the number of days you plan to stay and pay when you arrive.

Airbnb is a more expensive alternative, but a completely verified and totally reliable way to apartment-share. While I was traveling in New York, I stayed via Airbnb in a fantastic flat in Brooklyn: our hosts were so sweet and knowledgeable, told us where the best food was and how to order wine via delivery, and when the apartment was broken into and all our electronics were stolen, they completely reimbursed us the loss via the insurance they had through the site. Pretty slick. Slightly awkward at the time, completely resolved by the end.

Flights are best found through Kayak. It’s great to make a multi-city selection, as you can plan layovers in cool places and often find a cheaper flight. Sometimes I’ll search through Kayak to get an idea of which airline has the cheapest flight, and then go directly to the airline’s site, such as Aerlingus, United Airlines or Korean Air to find the same flight for slightly cheaper. Icelandair is pretty cool in that the government subsidizes layover flights through Iceland, in order to encourage tourism to the tiny isolated isle. It’s a super legit place to have a week to chill, but bring a tent if you’re budget-conscious. Be wary of China Airlines, as they give ZERO reimbursement if you cannot make the flight. NEVER buy a flight more than two months in advance. Every time I have purchased a cheap flight in advance, my plans have changed and I have to bite the bullet and suffer the loss. Be aware that buying cheap means no flexibility, huge charges to make changes, and potentially zero customer service (see Ryanair, local budget airlines from sites like Swoodoo, or Easy Jet).

Buses are the cheapest way to travel long-distance, and there are all sorts of incredibly cheap bus sites that vary via country. Megabus can get you from the UK to several key cities in Europe, such as Paris or Amsterdam, often overnight (which alleviates the need to pay for lodging) and is clean, easy, and has bathrooms onboard. Germany has recently has some legal shifts regarding rail monopolies over cities, and as a result a huge number of cheap bus companies have sprung up, nearly overnight: Meinfernbus is a great one, astoundingly cheap, the buses are brand new AND they sell cheap snacks onboard, if a nibbling need arises.

Hitchhiking is good in countries like Germany, the UK, Iceland, or Scandinavia, but it’s best to hitch with two, as you can put yourself into unpredictably bad situations with one. But the very best way of traveling overland is via carpool. I LOVE carpooling. I can’t rave enough about it. Though this brilliant communication system originated as a small cork-board office in Germany, you can also carpool France, which is also great to get through Spain. In France the carpools are generally empty, but the ride is comfortable and usually silent, unless you speak French well. The carpools in Germany are a riot, always full of Germans, and is a totally valid and acceptable way to painlessly arrange rides from city to city. It’s often cheaper and more enjoyable than buses, and is a great way to meet and talk with locals.

So, that’s about it for now. Enjoy your cheap, dirty travels, kids, they’re the best.

a glimpse of North Queensferry, Scotland

On Travel, and Stories.

Recently, as I was sitting at lunch with one of my dear friends, meeting her mother for the first time, we cracked open a bottle of wine and delved into stories. Travel stories, stories about people, about ourselves, about the past and how it leads into our hopes for the future. With the newfound presence of her mother, the lens to access these familiar stories was changed; a new perspective was present, which lead to an entirely new presentation and projection of these past experiences.

The truth is, most of my stories are largely untold. I travel to collect them, to garner these experiences which I tuck somewhere in the back of my heart, and they stumble out with strangers, occasionally with friends, and in short anecdotes or jokes, with family. I rarely know what stories I will tell. Sometimes I feel stuffed with so many stories that none of them will come out, that I’ll continually be an overstuffed cookie bear with all the cookies smashed up inside losing their shape and context. The chocolate melts into the dough and I can’t remember which flight it was, what country that was, who it was I shared that coffee with, where exactly this piece of clothing came from.

Yet, when I travel, my stories are vivid, they are present, they are shared. It is so easy to meet other travelers, some of whom have similar experiences, and what begins as a meeting turns into an exchange of memories. Details are sometimes so similar that one is able to immediately feel a connection with a stranger, and a greater web of connection between humanity is begun. It might be meeting a local from one of the countries I have traveled, such as meeting Germans in southern Spain, cracking jokes about Darmstadt and bananabier. It may be meeting another traveler who has had a similar experience, and in discovering such similarities we are able to instantly bond: such as meeting an Australian girl who was similarly berated at customs while trying to get into the United Kingdom, or meeting a French couple and exchanging stories and emotions about how families in Nepal were so incredibly willing to open their homes and their hearts, or meeting a Slovenian girl whose dream is to go to Korea. Sometimes it is merely a shared desire to go to a country: daydreaming about the mystical natural beauty of Laos; talking about Croatia or Greece or Turkey; getting lost in stories you’ve only heard from others about Costa Rica, or Peru, or Chile.

Sometimes the connection may consist of meeting someone from home who has similar mindsets and misses similar things. The nearness of your common heartbeat is a unique comfort: understanding the value of a hug over a kiss, missing traditional American-style coffee, talking about the beauty of lazy Minnesota cabin days and how summer on the lake may be the most perfect place in all the world.

I travel to learn empathy, to see the world through others’ eyes. I often forget the boundaries of my self when traveling, losing the edges of my American accent, passively following instead of speaking my mind, unable to decide on a place to eat despite hunger tearing up and receding into a dull ache as my feet pass restaurant after restaurant after restaurant, sometimes going to bed hungry because I just don’t feel like going to the effort of making a decision and eating alone.

Yet this aloneness is necessary to create experience, and the stories that result are what bring us together. It is the individual responsibility to garner and stitch together the basic framework of the stories, but it is the people we are lucky enough to meet and share our stories with that give us context, meaning, depth.

I travel to leave and I travel to return home. It is both the coming and the going that gives depth and growth to the human spirit, for it is necessary to understand and witness not only the cultures of others, but to view the culture in which one was raised and to see what is familiar through fresh, foreign eyes: to panic about wasting water as you listen to the sound of friends washing the dishes, to feel despair at the endless expansion of American suburbia, to question whether work ought to be the function and purpose of life, to understand the culture of food in entirely different ways, to question the immediate acceptance we have toward routines and habits that exist merely because, “That’s how it is, that’s how it’s always been,” instead of saying that things ought to be done differently because they could be done better.

The more I travel, the more I realize that there exists no one correct way to live; it is only the circumstances we have and the decisions we make and the priorities we choose that dictate the fullness, depth and experience of our life. It is what we choose to do with what we have, and how seriously we take our selves, the dreams and desires that come out of the heart, and how deeply we respect the lives of others in the decisions we make. Culture, values, food, and climate vary greatly; gender roles, hierarchies of respect, and freedom of decision culturally intersect at polar opposites across the world; the value of work versus play, the value of education, the value of health as a social or individual responsibility are starkly divided. But we are all human, we are all born and we will all reach the end of our life, where we will inevitably die. While spiritual, governmental, cultural and religious systems have all been created to deal with this system of life and death, and these vary greatly in context and practice, we the individuals are integrally, at our very core, the same.

It is my belief that the greatest thing which connects us, as humans, in facilitating understanding across all manner of boundaries, most especially when told with an open heart and mind (those of which create the ability to tolerate varying degrees and understandings of truth), is stories. Each of us is nothing but the stories we have. We need stories, to deepen our self and to connect us with others. Stories to help us remember who we are and to give us understanding of our role among others. We are nothing but the stories we have, and the whole experience of life is given meaning by our ability to share these stories with others.

If this were my rallying cry, I would cry: So go on, go out there! Wherever it is you must go. Live your stories and open your heart and share them with others. This is the life, this is what we have, it is our personal and individual duty to live it as best we can. One day, we will die. We will all die. And our stories will die with us. All we can do is share them now with the people we love. It is the best of what we have, and one of the only ways of understanding who and what we are. Make your stories, be your stories. And if you’re not happy with your stories, make new ones. This is it. Here we are. So go.

***

Are we all happy? John, my adopted English grandfather, asks Esther and me. Are we happy, is it fair? That’s what’s most important. We must be happy, and everything must be divided equally. Are you happy then, my dears?

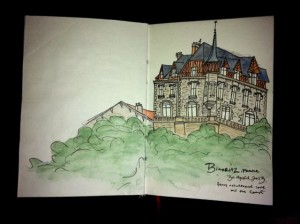

one last morning in Bordeaux.

Sunday morning, all the stores are closed. Blue skies and a light breeze, typically beautiful spring morning. Walk out to find some breakfast, hoping that a bakery is open, thinking of croissants. My stomach is twisted in the unique stress of having overstayed my welcome in this imposing city, massive white stone buildings towering in endlessly raised architectural tunnels along the streets, no trees in sight.

We exit the apartment through a heavy, ornate, dark blue door in the middle of the stone wall, stepping down immediately onto the street. Turn right and duck beneath construction, the narrow street lined on one side with perfectly parked cars. Bumper to bumper, practically no space between. At the end of the street the buildings clear and just ahead is a small island of flat, empty space sandwiched between two streets. In the space is a collection of white capped tents: a morning market.

There are six stands at the market. From right to left: crates of oysters, and old man making crêpes, a colorful array of fresh fruit. A local stand with an enormous variety of cheese: giant aged wheels, molding in shades of green to grey; small white, crusted cakes; hard, white triangles from which he shaves off chunks. Next to the cheese stand is a stand with rotisserie chickens, roasting on parallel vertical sticks; and beside this stand, breads. Enormous cakes of bread, weighed and sold by the kilogram: baguettes, croissants, brown breads, rye breads, white breads. Soft centers and hard crusts.

I buy a crêpe, spread thin across the griddle with a flat wooden tool, finished with a light sprinkling of sugar before it is folded into a triangle and handed to me on a napkin. We admire the fruits and walk to the bread stand, where the man cutting and weighing chunks of bread happily bounces around and laughs with his customers. He cheerfully educates my French-Canadian friend on the local Bordeaux french words for the butt of the bread: translated roughly to ‘corner’. Would you like the corners of the bread?, he asks me, in French, as he slices the remaining chunk bread in half and weighs my portion, before sliding it into a bag and handing it over to me with a wink and an enormous smile.

We walk back to the apartment, spirits considerably lightened. I book my last-minute ride from Bordeaux back to Biarritz, tearfully say goodbye to my host, give my final four kisses in Bordeaux and hop in the car to continue traveling on alone. Back to the Spanish border, where I rent a tent from the hostel and set it up cheerfully in the shaded shelter of the backyard in fading hours of the day, finally feeling the lightness of freedom. A bundle of white asparagus to cook for dinner, a leftover bottle of port from friends, an evening to sleep in the rustic, nostalgic comfort of a tent before dedicating to plans for what’s next.